In 2017, Universal tried to build a shared Dark Universe with its black and white monsters, beginning with The Mummy, starring Tom Cruise. Big actors were announced for multiple projects: Javier Bardem, Russell Crowe, and Johnny Depp. The Mummy missed the mark, trying to be a superhero movie instead of a horror, and the Dark Universe never manifested. Now Universal might be attempting once again, starting with Wolf Man, to make their Golden Age monsters into a shared universe.

Universal and Blumhouse are currently producing a remake of Wolf Man. Ryan Gosling was originally cast as the lead, but had to pull out and will be replaced by Christopher Abbott. Gosling is reported to still be attached to the film as an executive producer. Leigh Whannell, director of 2020’s The Invisible Man, will direct Wolf Man. With Whannell attached, Wolf Man is expected to be smart and tense. The Invisible Man surprised audiences with more than just a spooky movie, forcing viewers to question what is real and what is in the head of the lead, Cecilia, played by Elisabeth Moss.

With Wolf Man set to release in the fall of 2024, it is time to turn to the next entry in the Universal monster universe, and it is time to turn back to The Mummy – specifically, an abandoned take on the property by Clive Barker, writer and director of Hellraiser and Nightbreed. Barker is a master of horror, and horror had been the missing element in Universal’s modern takes on these monsters until The Invisible Man.

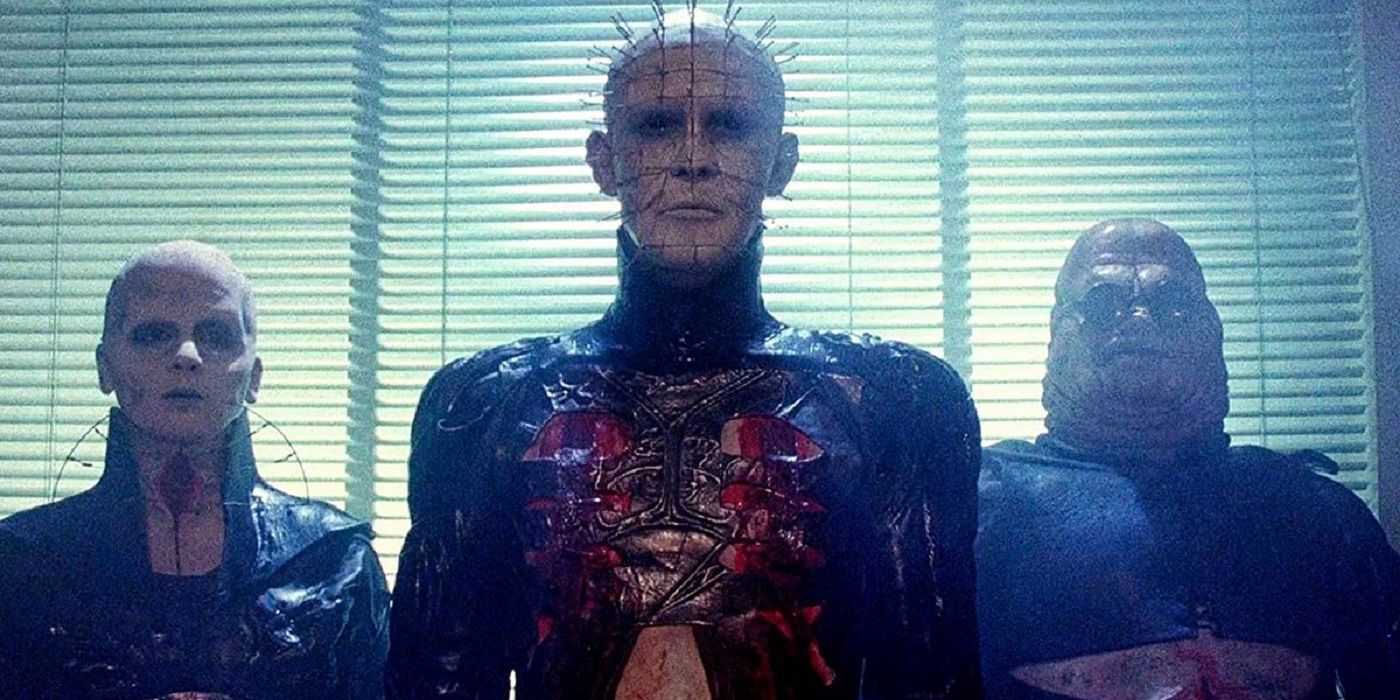

In 1990, years before the swashbuckling version of The Mummy we got with Brendan Frasier, Universal hired Barker to create a new take on the Egyptian monster tale that was born out of ideas for a Hellraiser sequel. Barker’s Hellraiser was already a modern Mummy, with the plot centered around Frank Cotton’s resurrection in the first film and Julia Cotton’s in the second, and with skinless Julia wearing full-body wraps as homage to The Mummy. Universal ultimately rejected the script by Barker and Mick Garris because it was just too bizarre for them. Isn’t the bizarre the whole reason for hiring Barker? Barker’s short stories and novels, like his movies, are charged with motifs of sexualism, transsexualism, body horror and metamorphosis. Barker’s obsession with ‘dangerous sex,’ as Proper Horrorshow describes his writing, was ahead of his time. Barker’s story for The Mummy and the art are still waiting, like pieces in a museum, to be dusted off.

Clive Barker’s Story

We only have pieces of Barker’s story, and the author is reluctant to reveal more, as he hopes the project will still be developed, with or without Universal. The idea originated as a story for Hellraiser 3, with the first cenobite being an Egyptian pharaoh. Barker is reported to have found the idea too good for Hellraiser, and saw the potential for crafting a whole other film franchise, which ended up being pitched to Universal.

What we know is that the script is set in a museum with an Egyptian exhibition involving an elaborate interior design for the attraction, not dissimilar to the museum plot of 1999’s The Relic, in which a theatrical kind of set is created as part of the promotion and entertainment of the displays.

Producer of the 1999 Mummy film, Jim Jacks, told Dreamwatch that the museum was going to be built in the shape of a pyramid, and the whole structure was designed to be an occult building. Jacks said, “Clive wrote kind of a Hellraiser thing, with a lot of dismembering – very bloody. It was about this guy who was head of a contemporary art museum built in the form of a pyramid. And he turns out be some kind of a cultist who’s trying to reanimate the mummies.”

The exhibition was not going to simply feature Egyptian aesthetics. Mick Garris described the museum exhibition set to Cinemafantasique, saying, “They brought an entire tomb and rebuilt it as it was originally in Egypt, recreated entirely within this Beverly Hills museum. It was almost like Chariots of the Mummies; in other words, the ancient Egyptians were inspired by and involved with alien intelligences from thousands of years before.”

The Egyptian design for the exhibition was to play a role in summoning the old gods. There is a little bit of Lovecraft in this story and a little bit of Barker’s own cenobites from Hellraiser/The Hellbound Heart. Describing the plot to Fangoria, Garris said, “The grand opening night ceremony is greeted with the meltdown, eruption and release of these creatures from beyond our planet.”

Garris described one of the mummies was to be a Lovecraftian alien similar to the Engineer demon seen in the first Hellraiser, saying, “There was a mummy that was actually wrapped about what was underneath – a rather arachnid-like, intelligent creature.”

The lead was supposed to be a thief, and we can assume there was a subplot around this character trying to steal an artifact from the exhibition. We can also take away from the details we have that the movie was intended to mostly be set within the museum and mostly over one evening, with the thief finding herself shut-in with attendees, again, like The Relic, as the mummies come to life and the horror show begins.

From Cenobites to Mummies

In the decades since the pitch to Universal was made, concept art for the project has found its way into the public eye, and it gives us a look at a truly original take on The Mummy that makes us regret that this movie was not produced. Barker’s mummies would have involved torturous body modification and binding, similar to his cenobites in Hellraiser.

The body modifications of the mummies were going to be reflected by the modern world of body modification in Beverly Hills — the plastic surgery industry that was just in its infancy in Hollywood in the early ‘90s. This theme of body modification through surgery would also be expressed with the lead character, who was to be revealed to have breast implants, and likely had facial surgery and the removal of the testes, but still had a penis.

Barker wanted to push the limits of horror and the ratings system with The Mummy. In 1990, Barker told Fear, “It will be a deeply perverse and dark movie. If anybody thought I’d given up my extreme pathological and psychotic moviemaking after Hellraiser, they had better think again. I’m going to the limits of the MPAA.”

Barker and Sexuality – A Transgender Lead

Clive Barker’s stories tend to focus on the human story and human drama – economic class division, gender transformation, abusive relationships, affairs, and divorce. His horror draws a link between the pain of being human and the metaphysical powers that are revealed in his stories. In Hellraiser, the cenobites only appear for a few minutes of the film, and Barker intended to structure his Mummy similarly, keeping the big monsters a mystery for the majority of the story.

Hellraiser is focused on Julia Cotton luring men to her home, while her husband is at work, and feeding them to her reanimated lover and brother-in-law. Hellraiser combines the discomfort of affairs, incest, murder, hiding bodies, and the threat of Julia’s husband discovering any of these activities.

With The Mummy, the human story was about the lead character’s transition from male to female through surgery and hormone treatment. This was not the first time Barker explored non-binary characters. His lead cenobite in The Hellbound Heart, the novella that Hellraiser was adapted from, was described as having an unclear sexual identity. In his short story, The Madonna, in Volume V of Books of Blood, two male characters have sexual encounters with water nymphs, which transform the men into women afterward.

The transgender subplot in The Mummy was not popular with Universal, and Barker pins the blame for the project’s failure on this specific subplot. Barker told Fangoria, “Looking back, our version of The Mummy was precisely what the Powers-That-Were at Universal did not want. It made the Mummy story over for the late twentieth century, not in terms of its effects (this was before CGI brought its dubious gifts to the process of horror film-making) but in terms of content. We had one particular narrative hook that we were very proud of. In the first scene, a strange boy-child is born, under circumstances (high howling winds and a ferocious thunderstorm) that suggest something unnatural is afoot.

The narrative then jumps twenty years or so, and we pick up the story of how sacred Egyptian artifacts are being brought to America for an exhibition that would put the Tutankhamun exhibit to shame. An uncommonly beautiful woman is threaded into the action, a seducer and a murderer of mysterious origin. Of the boy-child (now presumably grown to adulthood) we get no sight. Meanwhile, our anti-heroine is seducing her way through the male members of the cast, only to be revealed in the Third Act, as the boy-child, now turned (thanks to surgery and hormones) into a woman.”

Detailing the blockage he and Mick Garris ran into at Universal, Barker said, “Our creation was not welcomed at Universal, needless to say. The script, which Mick had labored hard over (working in a diminutive hotel room in London, which I visited daily for story conferences), was eviscerated by the script readers and our producers. How could we expect to get away with something so weird? Nobody in America, we were told, would accept such a ridiculous premise.”

Times have changed, and a story discussing this topic, while still taboo, is not so exotic as it was in the early ‘90s. Trans people are more visible in today’s society and media. The audience can believe this character to be real. While still divisive, the transitioning of genders is now widely and openly spoken about. Now is the time to explore this material in horror. Horror is supposed to shake norms and make audiences face things that they find uncomfortable, which is what Universal was afraid of doing 30 years ago.

In 1994, speaking at a convention, LA Weekend of Horrors, Barker said the intent with the transgender character was to cause male audiences to lust after the actress through the film and then reveal she has a penis near the end, introducing a new kind of internal horror of sexual confusion and self-betrayal to straight male audiences.

A History of Universal’s Mummy

Universal’s first take on the Egyptian monster came in 1932’s The Mummy, starring Boris Karloff as the titular proto-zombie. The film was inspired by the real-world superstition of the pharaoh’s curse, reignited by the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922, which was followed by the death of the expedition’s backer, Lord Carnarvon. The idea of mummies being resurrected predates Universal’s film. Bram Stoker published a mummy novel in 1903, Jewel of the Seven Stars. Stoker was not the first writer to explore mummy fiction. The genre goes back to Jane Webb’s 1827 novel, The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century.

Universal made four sequels to The Mummy, five if you count 1955’s Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy, and did not release a new mummy movie until Stephen Sommer’s action adventure film in 1999. Sommer’s movie spawned two sequels and a five-film spin-off series, The Scorpion King.

In 2017, Universal released its latest stab at The Mummy, again returning to the action genre. The film was poorly received by critics and only earned $410 million at the worldwide box office on a nearly $200 million budget. The failure of The Mummy forced Universal to ditch their plan for an action-oriented shared universe and have since turned to Leigh Whannell, who had critical and financial success with the low-budget, high-suspense reboot of The Invisible Man, to direct The Wolf Man.