A child is spirited away into a whimsical world populated by creatures as beautiful as they are bizarre. The journey ahead will see this child find meaning and wonder within themselves, their friends & family, and the world around them before they return to a familiar place. This is a broad synopsis, one that encapsulates the structural and thematic core of the major works of Japanese animation master and co-founder of Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki. While each of Miyazaki’s films offers a distinctive narrative, there is a singular question that unites his work: “How do you live?”

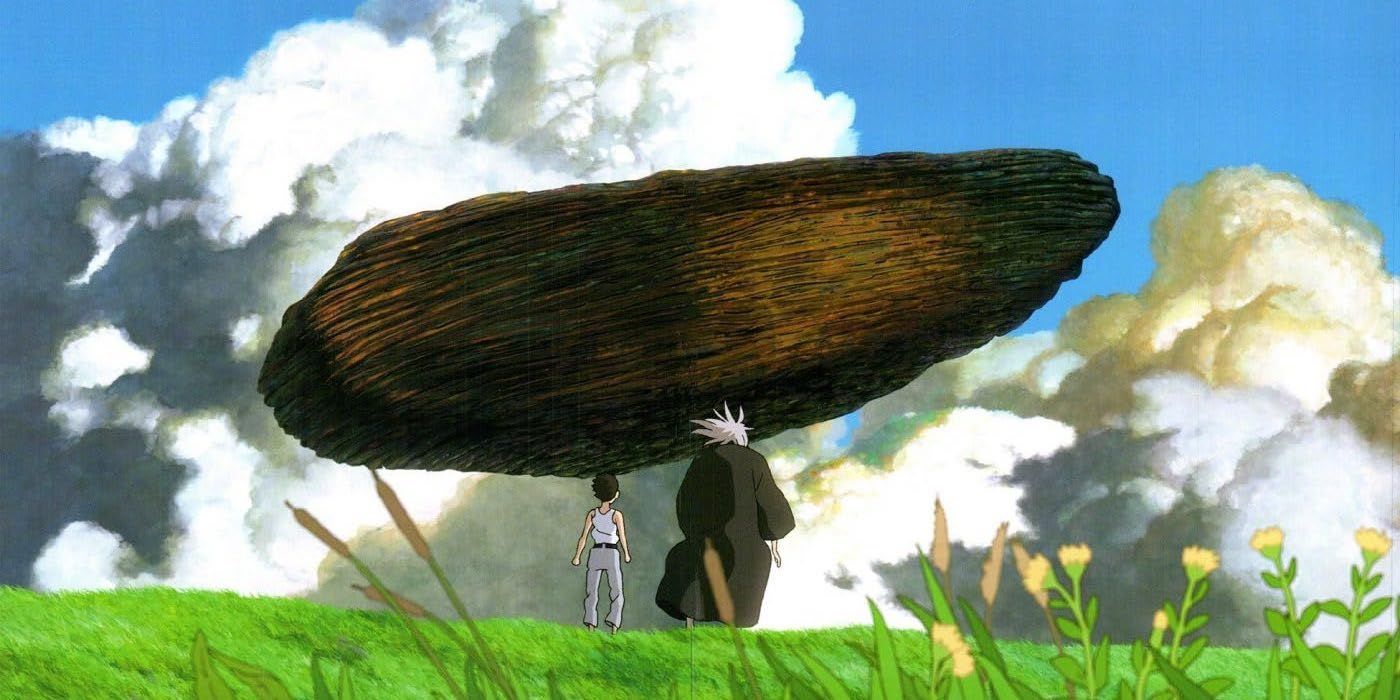

How do you live in wartime, when the environment is ravaged when you are a child coming of age in an unforgiving world, when you have experienced tremendous loss? This question was the original title of Miyazaki’s latest film, renamed The Boy and the Heron in the United States. The film follows a young boy named Mahito who lost his mother to a hospital fire during World War II. Mahito moves to the countryside with his father and aunt. Seeing visions of his mother, and followed by a Grey Heron making cryptic declarations about her fate, Mahito is ushered into a fantasy realm to potentially rescue her. This quickly unravels into a sweeping adventure through different worlds, to the place where the worlds themselves are constructed, in a surrealist and dreamlike fashion.

The Boy and the Heron is one of Miyazaki’s most complicated films, one which is difficult to wrap your arms around without a cursory understanding of the history of Studio Ghibli, and a willingness to accept that much of the film is open to interpretation. What is abundantly clear about this film is that he poured his own life onto the screen for us. This is far from the only time Miyazaki has pulled from his past in the making of his work, as his upbringing, family relations, and values bleed into every frame of his films. The movie is a vast, all-encompassing experience that is as thematically rich as it is a pure visual treat, destined to sit among his most iconic and beloved works.

What Happens in ‘The Boy and the Heron’?

In Miyazaki’s latest film, Mahito is coming of age in a tumultuous time, and finds himself on grand adventure that sees him coming to terms with his identity, the loss of his mother, and the nature of life itself. The movie has an overarching narrative, but often feels more like a series of chapters, separated by different settings and characters that don’t frequently overlap, save for Mahito.

Mahito enters a mysterious stone tower near his new home, guided by the heron referenced in the film’s title. The tower is revealed to be a liminal portal between worlds, and Mahito is taken from place to place on a journey of self-discovery that grants him closure for his mother’s passing. The movie is surreal and dreamlike, with sequences that are difficult to take at face value. This leaves the viewer in a position to interpret many of the movie’s strangest scenes on their own, to bring their own experiences to the table in sorting out exactly what Miyazaki is going for. But what is certain is that The Boy and the Heron is a compelling, provocative work from Miyazaki, one that pushes the audience to dig far below the surface.

‘The Boy and the Heron’ Reflects Miyazaki’s Life and Career

While the latest Studio Ghibli movie can be fairly inaccessible at a glance, Miyazaki pulls from his own life in the construction of its story. The Boy and the Heron is a fantastical, surreal story, but it draws on themes of coming-of-age and youthful angst which have been present in many of his most notable works, especially Spirited Away. The film’s ultimate intentions feel unclear until the themes of artistic expression, creation, and moving beyond loss come to a head. When Mahito follows the Grey Heron into a mysterious tower on a quest to find his mother, he eventually meets his wizard Granduncle, who is revealed to have created the fantasy world around them. Granduncle sits atop the tower in a liminal space seemingly outside tangible reality, constructing worlds with a series of differently shaped blocks stacked on top of each other.

Miyazaki is not known for his enthusiasm to speak to the press about his work, and his longtime producer and Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki often steps into the role of speaking on his behalf about the creative process and the meaning of his films. Suzuki identified many reflections of Miyazaki’s own life and career in The Boy and the Heron, explaining to IndieWire that Mahito was a self-insert for the director, and Granduncle was a stand-in for Ghibli’s other founder, the late director of Grave of the Fireflies and The Tale of Princess Kaguya, Isao Takahata. The relationship between Mahito and Granduncle, through Suzuki’s telling, reflects the working relationship between the two filmmakers, with Suzuki himself fitting in as the Grey Heron who sat in between the two. Takahata discovered Miyazaki’s talents and, as Granduncle offers Mahito control of the creation of these new worlds, enabled Miyazaki to tell stories of his own.

Per IndieWire, Suzuki explained that Granduncle’s role was reduced significantly out of grief over Takahata’s death in 2018. The film was early in the production stages at this time, and Miyazaki struggled to cope with the loss of this challenging, significant mentor figure and friend who had been reflected in the character. The character’s trajectory may also have indicated some reflections of Miyazaki’s thoughts about his own passing away, as it is easy to interpret Granduncle as a self-insert for the director if you lack the real-world context of Takahata’s influence and death.

Through the rearranging of these magical shapes, Granduncle crafts different realities that are full of both beauty and malice. As he reaches the end of his own time, he looks to Mahito as a potential successor, not to maintain his worlds but simply to carry on creating his own. Animation is, in essence, a rearranging of shapes as well, taking elements on a page or a screen that form movements, characters, and sprawling landscapes.

Miyazaki, and Takahata before him, hold onto these shapes in the hope that future generations will be inspired by their own ambitions and values to tell their own stories. Mahito rejecting Granduncle’s offer is a fascinating moment that reveals the ultimate concern for Miyazaki is that each person carves their own path, and chooses to live for themselves and their loved ones instead of following in the footsteps of those who came before them out of fear of things no longer being the same as they once were.

Hayao Miyazaki’s Past Work Draws From His Childhood, Personal Interests, and Values

The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s most direct instance of characters overtly designed to reflect his own life. However, his own upbringing and his current family dynamics are seen on the screen through many of Studio Ghibli’s child protagonists, his passion for aviation is everpresent in his fantastical stories, and his environmentalist, anti-war, and anti-consumer tendencies are at the forefront of many of his greatest works. While Miyazaki tends to make approachable and delightful stories, they are interwoven with resonant thematic content relating to everything he holds dear. He is an angry, cynical person in many ways, sickened by the damage we have done to this world.

Spirited Away is a movie that explores the direct consequences of environmental damage and consumer culture, how rapid industrialization and cultural changes have created a world that is inhospitable to the curious, innocent mind of a child. Princess Mononoke takes the environmental themes even further, in what is probably the darkest and most violent of Miyazaki’s works. The film forces viewers to reckon with the brutality we have put out into the natural world and argues that either on some tangible or spiritual level, there may be consequences for our mistreatment of nature.

Aviation is a passion of Miyazaki’s, one which recurs in many of his films. His father was the director of Miyazaki Airplane, a manufacturer of airplane parts used during World War II, which exposed Miyazaki to the complexities of aircraft at a young age. Porco Rosso, and The Wind Rises are the most notable examples. These films reckon with the admiration of these intricate, beautiful inventions which conflict with the destruction they bring when used as weapons of war. Flight is a recurring motif, even when planes are not involved in these films. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, Kiki’s confidence and maturation out of insecurity manifests in her ability to fly her witch’s broom. Flight is a sign of growth, freedom, and of dreams being achieved. As impossible as it may have seemed, even in our real world we have managed to build machines that can take flight.

The Wind Rises, aside from the ties to his love of aviation, is an especially important fixture in Miyazaki’s career, as the film is a biographical story of a real-life figure, but it reflects his concerns about the consequences of the work he does. It may seem strange for someone who devotes so much of his life to telling uplifting, heartening stories that have inspired and brought joy to children to be so preoccupied with the fear of what his work might do to the world, but this theme is even expanded on in The Boy and the Heron. Granduncle and Mahito both express concerns over how malice and darkness may compromise their ability to do their work purely. The malice spoken of in this new film may relate to Miyazaki’s reflection on his coldness or cynicism. He is a figure who has been noted for his pessimistic outlook on life. There is something curious about trying to understand the interior of an artist who is so hardened while making such bright, emotionally enrapturing images for us. One indicator of this is the nature in which Miyazaki writes about the strength of family in his work but has a complicated relationship with his own son, Goro Miyazaki. Goro has expressed that his relationship with his father was always strained and that his father felt Goro wasn’t ready when he made his film, Tales from Earthsea. Beyond this, Goro has expressed that he watches his father’s films primarily to understand him better, as Miyazaki had been distant and closed off for all of Goro’s young life, while his mother took charge of raising him.

The Miyazaki family dynamic is believed to be the inspiration for the family in Ponyo, the film Miyazaki made after Goro’s first was completed and after Miyazaki had claimed he was retiring for the first time. Ponyo follows a young boy named Sosuke whose father is away working on a ship, while his mother, Lisa, acts as the guiding force and primary source of love and affection in Sosuke’s life. Suzuki believes Sosuke is a model of young Goro, and that Ponyo was essentially an apology made to Miyazaki’s son for his failing to be a proper father. The film sweeps Sosuke into a beautiful friendship with a fantastical fish-human creature and sees Lisa guiding the two through perilous times while his father is away. In this light, Ponyo appears to be a retrospective pining for Goro to have had a better childhood, reflecting the remorse Miyazaki feels for pouring too much of himself into his work and not enough into his own family.

‘The Boy and the Heron’ Is a Heartfelt Summation of His Life’s Work

The Boy and the Heron pushes this self-insertion of Miyazaki’s regrets, aspirations, and ultimate reflections on life to new, complex limits. While Suzuki indicated that Granduncle is a stand-in for the late Takahata, the arc of this film and its placement within Miyazaki’s career seems to communicate Miyazaki’s own preparedness to let his work come to an end. On a Japanese TV program, Suzuki explained, as reported by IndieWire, that Miyazaki made this film as a means to tell his grandson that he is “moving on to the next world.” This re-frames the conclusion with the Granduncle as less about revisiting Miyazaki’s past and more about sorting out his own life coming to a close.

Miyazak has gone into retirement multiple times in the past, even claiming that he’d step down in 2001. While these claims have always been backtracked, Miyazaki did relinquish complete oversight of this film to Takeshi Honda, who oversaw the animation, while Miyazaki focused on storyboarding and the overall structure of the film. This indicates Miyazaki is winding down a long, storied career in animation, and that trajectory is reflected in Granduncle’s role as the world builder coming to an end. The stories Miyazaki makes are worlds unto themselves. Each one is a vast, dynamic, beautiful portrait of a deeply complicated figure. Miyazaki, who is cynical as ever while crafting the most whimsical stories, stories which emphasize the importance of family while having a wrought relationship with his own child, is a person made of contradictions between his artistic ventures and personal life. Yet his films all feel as though they have a unifying vision, distinct voices in perfect harmony.

His works are in harmony with one another, and The Boy and the Heron feels more in tune with the notion of the maker’s presence in their art than ever. The film questions the very nature of telling stories, of building worlds. It understands that these things must come to an end, and that it is okay, because something else will always come after. When Miyazaki’s worlds are eventually lost to time, as all things will be, they will have touched many people in their time. Miyazaki concludes that one should not live to build things to last, because nothing will. One should instead live to touch the lives of others, to love and grow and care for the world around us, to cherish it while it does last, because it will be gone before we know it. Miyazaki seems ready to put his work to rest, leaving behind decades of heartening, life-affirming stories, and one ultimate question for you to answer in the search for your own meaning: how do you live?

Is ‘The Boy and the Heron’ Truly Hayao Miyazaki’s Final Film?

With Miyazaki grappling so much with his own mortality, the loss of his mentor, and the finality of a long, storied life & career, The Boy and the Heron feels like a movie that could easily function as a swan song. The film feels like a natural final conclusion of Miyazaki’s prolific career, and he’s toyed around with the idea of retirement since before Spirited Away even came out.

But that is exactly why it is so hard to speculate on when/if Miyazaki will ever stop working. Some of his most seminal works came after he announced a retirement, including The Boy and the Heron. Every time he’s come out of retirement, he’s made a masterwork. So there is always room for another movie that will blow us all away. Imagine if Miyazaki had hung it up after Princess Mononoke, as he originally planned. No Spirited Away, or Ponyo, or The Wind Rises. It seems clearer with each subsequent release that Miyazaki will not quit until he can’t hold a pencil anymore, and we’re lucky to continue seeing whatever work he wants to show us. After giving the world so many beautiful stories, Miyazaki deserves to pursue whatever goal he wants, whether that is to keep working as long as he can, or to retire in peace.

The Boy and the Heron is currently available to stream on Max in the U.S.

WATCH ON MAX